Introduction

To begin this lesson, watch the short video below.

Now jot down all the things that you learned about the character in the video.

In “record” time (pun intended) and without dialogue, the animator reveals much about his character, including his approximate age, his devotion to the King (a.k.a., Elvis Presley), his impatience, and ultimately his ignorance of modern technology. We can all relate to the excitement of bringing home a new possession, the frustration of waiting for something you really want, and the urge to try anything to expedite a slow process. Of course, we, the superior tech users, sensed all along that this vinyl guy wouldn’t know what end was up.

Your focus in this lesson, however, will be on creating a short story character and narrator who can talk. You will learn how to reveal aspects of character through both direct and indirect characterization. With direct characterization, the author “tells” us about the characters and perhaps even himself or herself. With indirect characterization, the author uses clues such as appearance and action (similar to the video) and speech (unlike the video).

You will also learn the difference between flat and round characters, and you will create a profile for your own protagonist. To summarize, you will create the foundation for a complex and multidimensional character. Then, using the “Freytag’s Pyramid” graphic organizer you filled out in the lesson “Write an Engaging Story with Well-Developed Conflict and Resolution,” you will be able to begin drafting your short story.

Note: If you haven’t completed the lesson just mentioned, you may want to do so before starting this lesson.

Imagine 3-D Characters

Flat Stanley (shown in the picture on the right) might be a great portable travel companion, but he’s no model for a dynamic, round character. This nomadic, two-dimensional traveler is a flat character. If you travel with this static fellow to Cape Town, Paris, Mexico City, or Singapore, he returns home grinning, paper-thin, and unchanged. Some flat characters, however, like Mrs. Rossiter, the shushing housekeeper in Frank Sullivan’s “The Night the Old Nostalgia Burned Down: My Own New York Childhood,” are necessary when telling a story. The account you will read is a memoir.

Sometimes, when we kids came home from school, Mrs. Rossiter, the housekeeper, would meet us in the hall and place a warning finger on her lips. We knew what that meant. We must be on our best behavior. The wealthy Mrs. Murgatroyd was calling on Mother. We would be ushered into the Presence, Mother would tell us to stop using our sleeves as a handkerchief, and Mrs. Murgatroyd would laugh and say, “Oh Annie, let the poor children alone. Sure, you’re only young once.” Then she would lift up her skirt to the knee, fish out a huge wallet from under her stocking, and give us each $2,000,000,000.

Mrs. Murgatroyd is less stereotypical and flat than Mrs. Rossiter. As a result, Mrs. Murgatroyd is potentially more interesting. Based on Sullivan’s account, we know Mrs. Murgatroyd is wealthy, powerful, fond of children, and generous beyond measure. Suppose Sullivan wanted to write a fictional short story with this fascinating dowager as the protagonist. If he were going to develop Mrs. Murgatroyd into a character with dimension and depth, what would he need to know?

Perhaps he would ask the following questions:

- Is there a Mr. Murgatroyd?

- Where did she get her fortune?

- What does she look like?

- What is her relationship to the Sullivans?

- What prompted her visit?

An author gets to know a character by asking many kinds of questions. Beyond what you can infer from the account in “My Own New York Childhood,” what else might you want to know?

Think of two questions and write them using your notes. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see some possible responses.

Think of two questions and write them using your notes. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see some possible responses.

As you continue to ask and answer questions, the character of Mrs. Murgatroyd becomes more layered and better rounded. Now, what if she goes bankrupt after giving away so much money? What if our philanthropist is forced to give up her generous ways? What if her poverty forces her to wear old clothes and stockings with holes? In this scenario, Mrs. Murgatroyd would be forced to change. This change would be sad for the character on the page but would interest readers.

Images used in this section:Source: Flat Stanley, bigoteetoe, Flickr

Source: Lower Manhattan at Night from the Manhattan Bridge, NYC II, andrew c mace, Flickr

Show and Tell

In modern short stories, characterization is just as important as plot—or even more important depending on the kind of story you are writing. Yet a short story author doesn’t always have the space to tell the readers everything about the characters through direct characterization. Most writers of short stories use indirect characterization, demonstrating their characters’ qualities through speech, thoughts, and actions.

Through indirect characterization, the author shows us what the character is like; in direct characterization, the author tells or describes the character’s traits. You may already know the difference between these “show and tell” approaches with characters, but take a look at a classic example of the direct characterization of a monarch in “The Lady, or the Tiger?” by Frank Stockton.

In the very olden time, there lived a semi-barbaric king, whose ideas, though somewhat polished and sharpened by the progressiveness of distant Latin neighbors, were still large, florid, and untrammeled, as became the half of him which was barbaric. He was a man of exuberant fancy, and, withal, of an authority so irresistible that, at his will, he turned his varied fancies into facts. He was greatly given to self-communing; and, when he and himself agreed upon anything, the thing was done.

Notice the adjectives Stockton uses to describe the king and his ideas, beginning with “semi-barbaric.” To ensure that you understand this important adjective, the author defines it in a context clue—“the half of him which was barbaric.”

The next story provides an example of indirect characterization. It is an excerpt from James Barrie’s Peter and Wendy. We begin reading just as the Darlings are beginning a family. Look at the conversation that Mr. and Mrs. Darling have about the expense of caring for a child to see how Barrie characterizes Mr. Darling.

Wendy came first, then John, then Michael.

For a week or two after Wendy came it was doubtful whether they would be able to keep her, as she was another mouth to feed. Mr. Darling was frightfully proud of her, but he was very honourable, and he sat on the edge of Mrs. Darling’s bed, holding her hand and calculating expenses, while she looked at him imploringly. She wanted to risk it, come what might, but that was not his way; his way was with a pencil and a piece of paper, and if she confused him with suggestions he had to begin at the beginning again.

“Now don’t interrupt,” he would beg of her.

“I have one pound seventeen here, and two and six at the office; I can cut off my coffee at the office, say ten shillings, making two nine and six, with your eighteen and three makes three nine seven, with five naught naught in my cheque-book makes eight nine seven—who is that moving?—eight nine seven, dot and carry seven—don’t speak, my own—and the pound you lent to that man who came to the door—quiet, child—dot and carry child—there, you’ve done it!—did I say nine nine seven? Yes, I said nine nine seven; the question is, can we try it for a year on nine nine seven?”

“Of course we can, George,” she cried. But she was prejudiced in Wendy’s favour, and he was really the grander character of the two.

“Remember mumps,” he warned her almost threateningly, and off he went again. “Mumps one pound, that is what I have put down, but I daresay it will be more like thirty shillings—don’t speak—measles one five German measles half a guinea, makes two fifteen six—don’t waggle your finger—whooping-cough, say fifteen shillings”—and so on it went, and it added up differently each time; but at last Wendy just got through, with mumps reduced to twelve six, and the two kinds of measles treated as one.

As you read this excerpt, what do you learn about Mr. Darling’s character? How do you come to know these things about him? If you answered that he’s a man totally absorbed in accounting for the last cent, you would be correct. Barrie shows us this by first describing his actions, holding his wife’s hand while doing the absurd calculations that will determine whether they can keep the baby. Next, Barrie has Mr. Darling speak absurdly while he adds up figures and tries to fit Wendy into the budget. Barrie has him continue to add the cost of all the childhood illnesses that she might encounter. At the last moment, she comes in under the bottom line.

As Barrie characterizes Mr. Darling, readers get a feel for how this character speaks, thinks, and looks. They also see his actions and get a taste of how other characters react to him. Including as many of these methods as possible is an important step in creating a dynamic, round character who is ultimately believable.

The STEAL mnemonic helps you remember ways you can show your imaginative characters to your readers:

| Speech | What does the character say? How does the character speak? |

| Thoughts | What is revealed through the character’s private thoughts and feelings? |

| Effect on others | What is revealed through the character’s effect on other people? How do other characters feel or behave in reaction to the character? |

| Actions | What does the character do? How does the character behave? |

| Looks | What does the character look like? How does the character dress? |

Using the STEAL chart above and Darling as your model, answer the questions posed. Write your responses using your notes. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see some possible responses.

Using the STEAL chart above and Darling as your model, answer the questions posed. Write your responses using your notes. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see some possible responses.

Images used in this section:Source: (Harry Clarke) HEROD & HERODIAS, Fergal of Claddagh, Flickr

Source: Peter Pan 1924 movie, Wikimedia Commons

Source: 155/365 - peter pan, jypsyjen, Flickr

Build Your Main Character

Stephen King writes that the job of building characters in fiction “boils down to two things: 1) paying attention to how the real people around you behave and 2) telling the truth about what you see. You may notice that your next-door neighbor picks his nose when he thinks no one is looking. This is a great detail, but noting it does you no good as a writer unless you are willing to dump it into a story at some time.”

“Fiction,” according to author Flannery O’ Conner, “is an art that calls for the strictest attention to the real,” perhaps including some disgusting details, as in King’s example. If you want to have readers—and all writers want readers—you have to create real and nuanced characters. This means you must add details that readers will recognize in themselves or others.

In Peter and Wendy, Barrie shares details about the “real” world of Mr. Darling that reinforce our assessment of his character. We have a pretty good idea about Mr. Darling’s character based on speech, actions, and effect on others. These details help us believe that someone like Mr. Darling could really exist (odd though he might be). The reason is that believable characters act in ways that are grounded in reality, which adds to the verisimilitude of your story.

(Note: Before you do the next exercise,

you may want to review the plot exercise you did using Freytag’s Pyramid in the graphic organizer for the lesson “Short Story with Well Developed Conflict and Resolution.” If you have not yet read this earlier lesson, you may want to review it and do the exercises after completing this lesson.)

Now you will fill in a graphic organizer labeled “Cast and Type of Characters.” You need to give your protagonist an authentic-sounding name. If you select something like “Dudley Do Right” or “Snidely Whiplash,” no one will take you seriously. K. M. Weiland, who writes a blog called “Wordplay: Helping Writers Become Authors,” offers advice about naming characters. Click on the link and scroll to page 20 of the e-book to read the advice. Afterward, download the graphic organizer below.

You can save, download, and print the graphic organizer. When you are finished with it, return to this section. Graphic Organizer InstructionsNames are important. Mention a name and instant preconceptions spring to mind. Although our names may not play a role in shaping our personalities, they certainly can reflect our background, ethnicity, even our religion. They may even define our relationships. So it should come as no surprise that naming a character is an important moment in defining the personality of the character and the role he or she will play in a story.

“You can never know enough about your characters,” claimed novelist W. Somerset Maugham. In this section of the lesson, you will spend some time getting to know your protagonist so you don’t end up with a stereotype, like a Disney princess or a Marvel comic superhero. Also, if you profile your character carefully, you’re less likely to develop inconsistencies that might ruin the verisimilitude of your story. For instance, if your plot requires a physically taxing feat, you may not want to add potato chips and donuts to your protagonist’s daily diet. Similarly, if your protagonist needs the observational skills of a detective, you may not want to make him absentminded.

You can print out the graphic organizer and use it as a guide as you begin writing your story and developing your characters. Use your knowledge of the entire character to decide what the character would do in certain situations, and how other characters might react.

Images used in this section:Source: stephen (ba) king powder, Rakka, Flickr

Source: Dudley Do-Right, Alex Anderson, Wikipedia

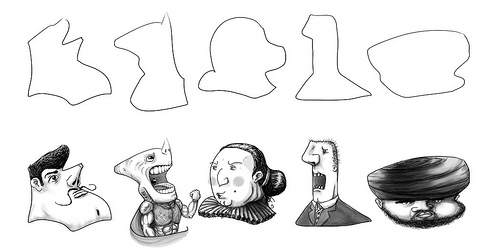

Source: Villainc, J.J. Wikimedia

Source: Characters Week 4, Murtada al Mousawy, Flickr

Read about a Main Character

Every short story requires a central character or protagonist who is motivated to take action or react to an outside force to achieve some purpose. In O. Henry’s story “A Retrieved Reformation,” the central character is Jimmy Valentine. In the first part of the story, we know him as Valentine, 9762, a parolee with superb safecracking skills. In the section you are about to read, Jimmy adopts an alias—not a surprising move for an ex-convict with no intention of going straight.

O. Henry uses direct characterization to tell us some things about Valentine. For instance, he writes that Jimmy “had won the respect of the community,” and “his shoe-store was flourishing.” Most of what we know about Jimmy’s character, however, is revealed through his thoughts, actions, and others’ reactions to him.

Click the link to read the story “A Retrieved Reformation.” See if you can identify the places where Jimmy's character is revealed.O. Henry employs both direct and indirect characterization to divulge information about his dynamic protagonist, Jimmy Valentine. Remembering the acronym STEAL—an apt mnemonic for a story about a safecracker—helps us see all the indirect ways this skillful author brings Jimmy Valentine to light.

For the next exercise, the sentences in the story have been numbered to enable you to reread quickly. Decide which STEAL method (Speech, Thoughts, Effect on others, Actions, or Looks) method reveals the described character trait(s) or action(s). Remember: minor characters in the story, such as the antagonist Ben Price, can also divulge information.

As you begin thinking about your own short story, you might want to think about how you can use indirect and direct characterization. If O. Henry used direct characterization to describe everything we know about Jimmy, the story would be longer and much less interesting. Think about how you will use indirect characterization in the story you are getting ready to write.

Images used in section:Source: WDJones1stMugAt15, FBI, Wikimedia

Draft Your Story

Now that you’ve outlined an intriguing plot in the previous lesson and fleshed out your protagonist in this one, all you need to do is start writing a draft of your short story. Don’t feel burdened to get everything perfect in your first draft. Use your plot outline from the previous lesson and your character profile to write steadily to the end. On your first try you won’t be able to incorporate everything you learned, but the following reminders of effective characterization may help you stay on track:

- Make sure your characters, no matter what their personalities are like, come across like real people.

- When you can, show your readers something about your character; when you can’t, tell them something.

- Give your readers a reason to care about what happens to your character.

- Describe your minor characters with one or two modifiers, and save your most impressive descriptive powers for your protagonist.

The art of the short story is to share truth about the human condition or human nature. It is also to entertain and provide pleasure for a reader. A well-written short story fulfills these dual obligations. Keep this in mind as you begin work on the draft of your short story.

Images used in this section:Source: day 41 . . . homework, katyhutch, Flickr

Resources

Bailey, Tom. A Short Story Writer’s Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2001.

Barrie, James. Peter and Wendy. Project Gutenberg. 2008.

//www.gutenberg.org/files/26654/26654-h/26654-h.htm.

“Defining Characterization.” Readwritethink.org. Accessed Oct 4, 2012.

//www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson800/Characterization.pdf.

Gioia, Dana, and R.S. Gywnn, eds. The Art of the Short Story. New York: Pearson Longman, 2006.

Henry, O. “A Retrieved Reformation.” In Roads of Destiny. Project Gutenberg.

//www.gutenberg.org/files/1646/1646-h/1646-h.htm#10.

Hood, Dave. “Character and Characterization in Short Fiction.” Find Your Creative Muse (blog). April 20, 2011.

//davehood59.wordpress.com/2011/04/20/character-and-characterization-in-short-fiction/.

King, Stephen. On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. New York: Pocket Books, 2000.

Stockton, Frank. ”The Lady or the Tiger?” In A Chosen Few. Project Gutenberg. 2008.

//www.gutenberg.org/files/25549/25549-h/25549-h.htm#tiger.

Sullivan, Frank. “The Night The Old Nostalgia Burned Down.” New Yorker, May 25, 1946.

Thomson, Amy Restivo. “Elemental Fiction.” Trinity University. August 1, 2011.

//digitalcommons.trinity.edu/educ_understandings/162.

Weiland, K.M. Crafting Unforgettable Characters. KMWeiland.com. E-book.

//www.kmweiland.com/wp-content/uploads/crafting-unforgettable-characters.pdf.