Introduction: Hey, What’s the Big Idea?

Source: Lule neLamp, Bessi, Wikimedia Commons

It's the night of the big concert. You’re sitting in the trumpet section, first chair. Your solo is coming up, and you begin to sweat. Your band director conducts the opening section, then turns to you, smiling. Everyone is waiting for your solo to begin. Instead of a beautiful sound, though, out comes a flurry of wrong notes. After the solo, you shoot an embarrassed glance up to the podium, only to see that your band director’s happy smile has turned to a very unhappy frown. “I should have practiced a lot more,” you tell yourself.

In the scene above, a student realizes that he should have been more prepared for a certain task. You might say that he learned a lesson: Always be prepared. Sometimes life presents us with experiences that, in the end, teach us a lesson to take forward in life.

Source: American students from Matthew C. Perry High School and Japanese students from Iwakuni Municipal Higashi Junior High School play their musical instruments together during the inaugural U.S.-Japan Friendship Concert Sunday at Iwakuni Sinfonia Concert Hall. Cpl. Claudio Martinez, Wikimedia Commons

Almost everything you read—novels, plays, short stories, poems, and essays—have some sort of lesson or insight that the writers want us to understand. They write stories about people who come face-to-face with some of life’s big challenges. These stories have to do with a larger view of life, an idea about what it means to be a human being. In the world of literature, these big ideas or larger views are called themes.

In this lesson, you will learn how to discover a story’s theme and distinguish it from the story’s subject matter, its topic.

Fables and Morals

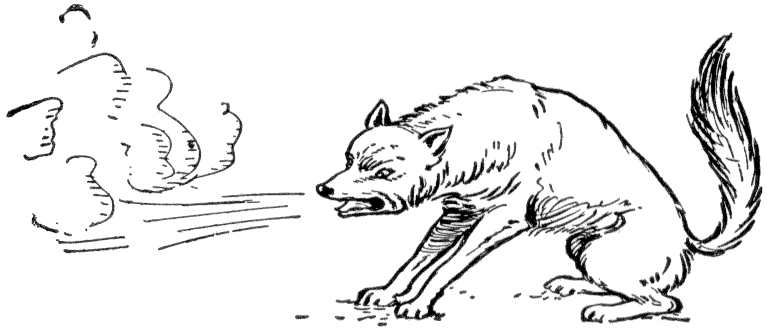

Source: Aesop, Milo Winter, Project Gutenberg

We're going to begin our study of theme by looking at fables. Fables are stories about people and animals who face pretty ordinary problems. How those problems are solved is part of the theme. In fables, the theme is explicit. You are told at the end what the theme of the fable is.

Let's begin to practice finding the theme of a story by looking at a few fables where the theme is told to you at the end to make sure you “got it”!

Sometimes the theme of a fable is called the moral. Click on the link to view a short video of the fable “The Ant and the Grasshopper.” After you watch the video, read the text below.

At the end of this selection, notice the highlighted sentence. That's the theme, or the moral, of the story. It's given to you explicitly.

In a field one summer’s day, a Grasshopper was hopping about, chirping and singing to its heart’s content. An Ant passed by, bearing along with great toil an ear of corn he was taking to the nest.

“Why not come and chat with me,” said the Grasshopper, “instead of toiling and moiling in that way?”

“I am helping to lay up food for the winter,” said the Ant, “and recommend you do the same.”

“Why bother about winter?” said the Grasshopper. “We have plenty of food at present.”

But the Ant went on its way and continued its toil. When the winter came, the Grasshopper had no food and found itself dying of hunger, while it saw the ants every day distributing the corn and grain they had collected in the summer. Then the Grasshopper knew it was better to work now and play later because being prepared is always a good idea.

Read the last sentence again. Do you see how the author comes right out and tells you what the big idea (theme) of the story is? The moral of the story, its theme, is explicitly stated.

Now, you try it. Remember, the theme of a fable is sometimes called its moral and is explicitly stated in the text.

Click below to hear another of Aesop’s fables called “The Bundle of Sticks.”

Source: A bundle of sticks, Heinrich Zille Herbst, Wikimedia Commons

What is the theme of the story? When you have an answer, click on Check Your Understanding below to view a few sample responses.

Now that you know that a theme is an author’s big idea for the reader and that sometimes the big idea of a text is stated for you (as in the case of the morals in fables), let’s move on to themes that need a little more work to uncover. We’ll start with some examples from children’s literature.

How to Figure Out the Theme(s) of a Story

Source: The Three Little Pigs, Leslie Brooke, Project Gutenberg

There are some helpful ways to figure out the themes of a story when they are implicit. You know from our discussion of “The Three Little Pigs” that you have to do some thinking about what your own experiences are and connect them to the events and characters in the story. You have to infer, or make some good guesses, about the theme based on the information that you’re given. One simple way is to follow this four-step process:

- Find the topic, the subject, of the story. See NOTE below.

- Figure out how the topic helped the character(s) grow or change.

- Make this into a general statement on life by taking out the specific characters and the specific plot of the story. For example: People (pigs) who plan ahead (build brick houses that are safer) are sometimes better able to keep bad things (wolves) from happening.

- Check your process by answering the questions

- Does the theme mention a specific character? (Answer should be NO)

- Does the theme talk about plot at all? (Answer should be NO)

- Could the theme apply to another story? (Answer should be YES)

NOTE—To find the topic of a story, pay attention to the story’s elements and ask questions like these:

- Who is (are) the main character(s)?

- What happens to them?

- Do their thoughts and feelings change during the story? If so, what or who makes them change?

- Are there any issues that arise more than once in the story? (This gives you clues about what the author might be concentrating on in the story.)

Now, let’s practice finding a theme using inference. Read the following text, and when you’re finished, write a theme statement for it. Use the chart below to check if what you’ve written sounds like a theme. You can then click on Check Your Understanding after the chart to see some possible responses.

Source: Basketball through the Hoop, Cyrus Andiron,

Wikimedia Commons

In his sophomore year of high school, Henry Williams tried out for the varsity basketball team at Hoggard High School in Buda, Texas. But at five feet and eleven inches tall, the coach believed that Williams was too short to play at that level, so he was cut from the team. Williams was disappointed and hurt, but he didn’t let this obstacle defeat him. In fact, it pushed him to work even harder. He trained vigorously and grew another four inches the following summer. When he finally made the varsity squad, Williams averaged 25 points a game and went on to become the highest scoring player for the Dallas Mavericks.

Here’s a graphic organizer for checking your theme.

Is your theme the real deal?

| Question | Response | Theme or Not a Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Does your theme statement mention specific characters? | No | So far, it could be a theme. |

| Does your theme statement talk about the plot? | No | Good! It still could be a theme. |

| Could your theme statement apply to another story or anyone else’s life? | Yes | Bingo! It sounds like you might have a theme. |

Your Turn

Source: Temporary Works Road Sign in Quebec, Quebec

Transports

Read the following excerpt from a short story by Gary Soto. When you finish reading, try to identify the theme of this excerpt. You might want to look back at the chart to ask yourself questions about your theme statement. Click on Check Your Understanding after the story to see some possible responses.

The story begins on the first day of 7th grade. Victor plans to study French, mainly because he has a crush on Teresa, a girl in his grade. The excerpt begins on the first day of French class as Victor works to impress Teresa.

They were among the last students to arrive in class, so all the good desks in the back had already been taken. Victor was forced to sit near the front, a few desks away from Teresa, while Mr. Bueller wrote French words on the chalkboard. The bell rang, and Mr. Bueller wiped his hands, turned to the class, and said, “Bonjour.”

“Bonjour,” braved a few students. . . .

Mr. Bueller asked if anyone knew French. Victor raised his hand, wanting to impress Teresa. The teacher beamed and said, “Tres bien. Parlez-vous francais?”

Victor didn’t know what to say. The teacher wet his lips and asked something else in French. The room grew silent. Victor felt all eyes staring at him. He tried to bluff his way out by making noises that sounded French.

“La me vave me con le grandma,” he said uncertainly.

Mr. Bueller, wrinkling his face in curiosity, asked him to speak up.

Great rosebushes of red bloomed on Victor’s cheeks. A river of nervous sweat ran down his palms. He felt awful. Teresa sat a few desks away, no doubt thinking he was a fool. Without looking at Mr. Bueller, Victor mumbled, ‘Frenchie oh wewe gee in September.”

Mr. Bueller asked Victor to repeat what he said.

“Frenchie oh wewe gee in September,” Victor repeated.

Mr. Bueller understood that the boy didn’t know French and turned away. He walked to the blackboard and pointed to the words on the board with his steel-edged ruler. . . .

Victor was too weak from failure to join the class. He stared at the board and wished he had taken Spanish, not French. Better yet, he wished he could start his life over. He had never been so embarrassed. He bit his thumb until he tore off a sliver of skin.

The bell sounded for fifth period, and Victor shot out of the room, avoiding the stares of the other kids, but had to return for his math book. He looked sheepishly at the teacher, who was erasing the board, then widened his eyes in terror at Teresa who stood in front of him. “I didn’t know you knew French,” she said. “That was good.”

Mr. Bueller looked at Victor, and Victor looked back. Oh please, don’t say anything, Victor pleaded with his eyes. I’ll wash your car, mow your lawn, walk your dog—anything! I’ll be your best student, and I’ll clean your erasers after school.

Mr. Bueller shuffled through the papers on his desk. He smiled and hummed as he sat down to work. He remembered his college years when he dated a girlfriend in borrowed cars. She thought he was rich because each time he picked her up he had a different car. It was fun until he had spent all his money on her and had to write home to his parents because he was broke.

Victor couldn’t stand to look at Teresa. He was sweaty with shame. “Yeah, well, I picked up a few things from movies and books and stuff like that.” They left the class together. Teresa asked him if he would help her with her French.

“Sure, anytime,” Victor said.

“I won’t be bothering you, will I?”

“Oh no, I like being bothered.”

“Bonjour,” Teresa said, leaving him outside her next class. She smiled and pushed wisps of hair from her face.

“Yeah, right, bonjour,” Victor said. He turned and headed to his class. The rosebushes of shame on his face became bouquets of love. Teresa is a great girl, he thought. And Mr. Bueller is a good guy.

He raced to metal shop. After metal shop there was biology, and after biology a long sprint to the public library, where he checked out three French textbooks.

He was going to like seventh grade.

Now that you’ve finished the lesson and moved from ants and a grasshopper, to pigs and wolves, to kids in real life situations, you will discover that finding the theme when you read makes reading much more exciting and worthwhile.

Resources

Resources Used in This Lesson: Bibliography

“The Ants and the Grasshopper—Aesop’s fables.” HooplaKidz. YouTube video, 1:01. Posted October 12, 2012. http://youtu.be/YT5DnTKm3YE.

Cerza, Michael. “Bundle of Sticks.” Character Trax. Compact Disc. Nearvarna Records. 2000.

“Fairy Tales—The 3 Little Pigs Story.” KiddoStories. YouTube video, 3:19. Posted July 27, 2014. http://youtu.be/CtP83CWOMwc.

Soto, Gary. “Seventh Grade.” http://iblog.dearbornschools.org/dobertn7/wp-content/uploads/sites/405/2013/11/seventh.grade_.by_.gary_.soto_.pdf.